In pursuit of sustainable tuna fisheries in the western and central Pacific Ocean (WCPO), the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC) members agreed in 2015 to a workplan for the adoption of harvest strategies for WCPO skipjack, bigeye, yellowfin and South Pacific albacore tuna. A critical element of this initiative is capacity building, where stakeholders play an important role in leading the development process by making key decisions. The Pacific Community (SPC), serving as the science provider of WCPFC, has been supporting this effort and since 2018 has provided training on harvest strategies through regional and national workshops. In order to assess the use and application of the information and knowledge provided to participants through these workshops, a tracer survey was deployed in 2023. This article presents some of the findings of this survey, shedding light on the challenges that are present after the facilitation of a workshop and why, even though knowledge increases with training, this does not necessarily mean that application of learnings will follow.

Sustainable management of tuna: why adopt a harvest strategy?

The WCPO region hosts the world’s largest tuna fisheries industry, which contributes significantly to the economy and the livelihoods of PICTs. Despite its vital significance, the existing management systems employed in the tuna fisheries appear to be reactive, and with short-term objectives, which jeopardises the sustainable management of such a large-scale industry.

The deficiencies of the current management systems indicate that there is a pressing need for a structured system that can provide clear guidelines and focus on long-term objectives encompassing all stakeholders. Responding to this urgent need, the WCPFC has introduced a harvest strategy approach to better manage the tuna stocks in the region. A harvest strategy is a formalised and pre-agreed framework for guiding decisions on the management of a fishery. It aims to shift from short-term, ad hoc decision-making to a longer-term proactive approach to achieve defined management objectives. This shift in approach is crucial to effectively address the challenges posed by the scale and complexity of the industry, ensuring sustainable practices and equitable benefits for all involved parties in the WCPO region.

SPC delivery approach of harvest strategy training

A key component to the adoption of the harvest strategy approach is to conduct stakeholder engagement and capacitybuilding activities. Across the development process, stakeholders are expected to take the lead by making a variety of data-driven and science-based decisions. Many of these decisions require a two-way dialogue between scientists and decision makers from PICTs.

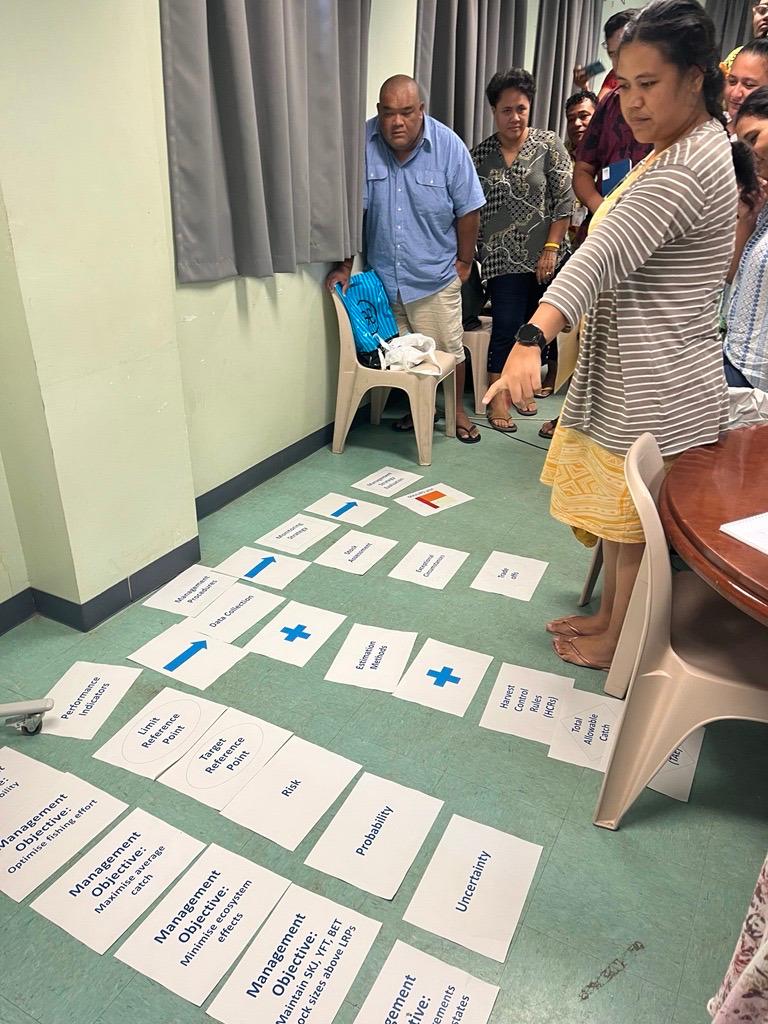

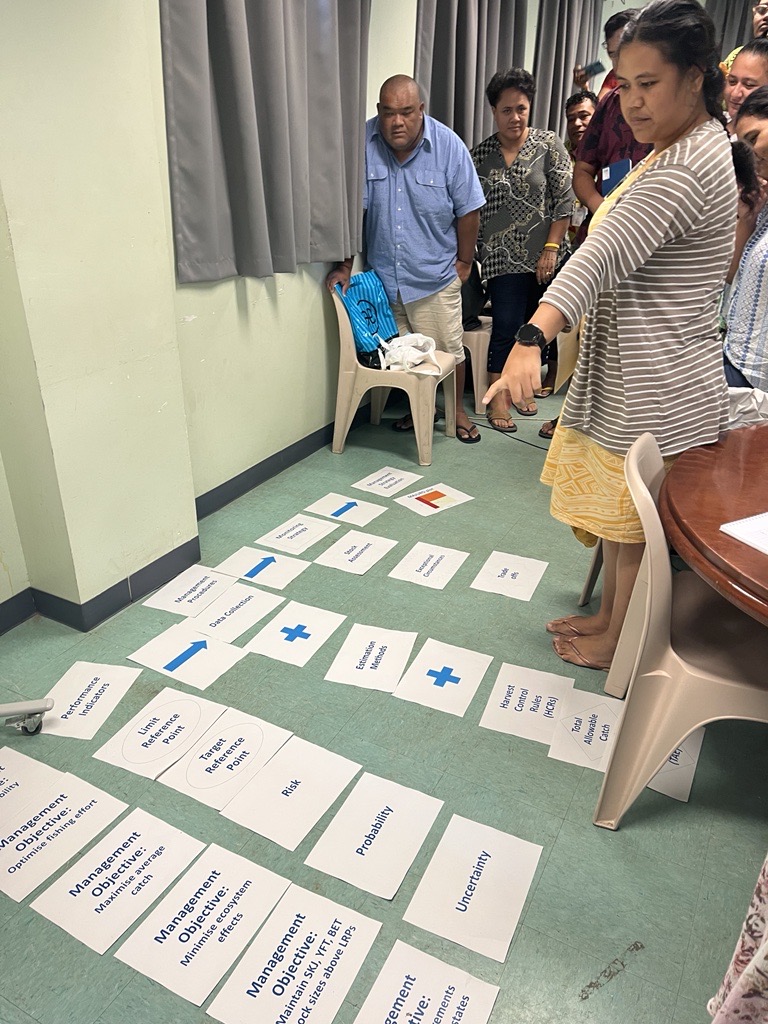

SPC facilitates the capacity-building process by organising 2–3-day national workshops, offering participants a comprehensive overview of the harvest strategy approach. The objective of these workshops is to equip participants with the knowledge needed for effective decision-making throughout the process. Additionally, they serve as a valuable platform for stakeholder communication.

Since 2018, 18 workshops on harvest strategies have been conducted by SPC. At least 400 participants have been trained during these workshops, coming from 12 PICTs (Cook Islands, FSM, Fiji, French Polynesia, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Palau, PNG, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tokelau and Tonga). Some of the workshops have been done in collaboration with the Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA), delivered at both national and regional levels. In addition, SPC’s Fisheries, Aquaculture and Marine Ecosystems has also facilitated three informal two-hour on-line workshops on national-specific topics with French Polynesia, New Caledonia and China in 2023.

The provision of the harvest strategy workshops has increased the understanding of this approach among PICTs. The workshops have been a valuable step that contributed to the adoption of the interim skipjack management procedure (MP) at the WCPFC meeting in December 2022. This marks the first instance of a harvest strategy approach being adopted in such large-scale fisheries. It stands as a significant decision to ensure the ongoing sustainability of the stock while improving the transparency and effectiveness of management.

Methodology of the tracer survey

Having considered the significant efforts that SPC has made to engage members in developing harvest strategies, we employed a tracer survey with participants to assess the potential application of knowledge of harvest strategies, and to understand the challenges they have faced in the use of this fisheries management approach. Tracer surveys are conducted with participants after some time (six months, a year, two years) has elapsed since the completion of the training. These are tools to capture data on the potential use of the learnings gained from a training workshop or how the context/situation changed following the completion of the workshop.

Four training events on harvest strategies were selected (two in 2022 and two in 2023), targeting 44 unique participants. These training workshops were held in Brisbane, Kiribati and Samoa (in person) and one was delivered online with participants from French Polynesia. We implemented a mixed-methods approach: most participants (82%) were invited to fill in the survey directly (self-administered survey) while the remaining 18% of participants were invited to receive a call with the surveyor to go through the questionnaire with them (assisted/guided survey). The harvest strategy tracer survey was deployed on 2 November 2023 and reminders were sent on both 13 and 22 November 2023.

From increasing knowledge to applying learnings – the missing link

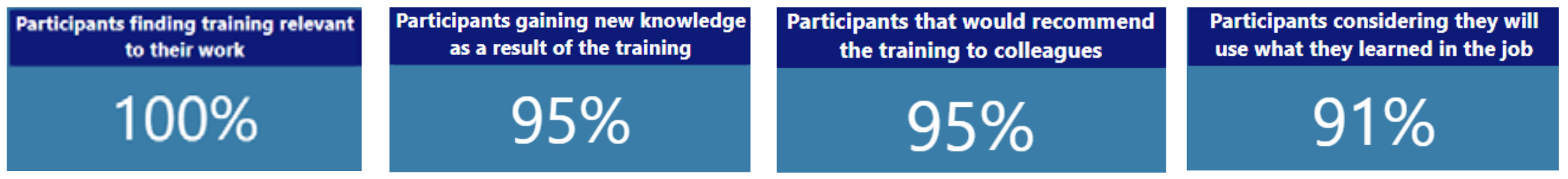

A first review was done on the data collected from the post-training survey, which tends to be conducted immediately after the training is delivered. This initial survey collects information on the participant’s impressions of the content, perceived increase of knowledge, relevance to the participant, and overall satisfaction with the training

The aggregate response ratio was 48%.1 As tends to be the case with training and capacity-building activities, the immediate feedback from participants was mostly positive. On average, the training content was rated 4.6 out of 5, all respondents found the training relevant to their work, and 95% of them gained new knowledge as a result of the training.

The initial positive reaction contrasts with the actual responses received six months or more after attending the training via the results of the tracer survey. SPC received 16 responses to the harvest strategy tracer survey, representing a 36% response ratio to the total participation in the selected training to be assessed.2 Out of the total respondents, 31% indicated they had applied the learnings on harvest strategies in their work. This figure represents a substantial drop from the increase in knowledge reported immediately after the training.

“Our ministers are very revenue-generated thinkers, so it had a clash with conservation and fisheries development, that’s the current discussion” Female participant from Samoa.

Participants were asked about the challenges they faced in the application of the knowledge of harvest strategies; responses reported included:

- lack of policy and regulations in place to advance the use of the knowledge at the national fisheries sector,

- trade-offs faced by decision-makers,

- need to develop long-term objectives,

- lack of general understanding of the importance to sustainable management practices, and

- specific components of the strategy (model complexity, validation, generalisation and uncertainty).

“Lack of awareness and understanding about the importance of sustainable harvesting practices can lead to unsustainable resource use. Public education and outreach are crucial components of effective harvest management” Female participant from Kiribati.

Despite participants reporting an increase in the understanding of the harvest strategies, the responses relating to the challenges seem to indicate that this is not always shared. Within the context of the respondents’ work, it is possible that decision makers and other stakeholders do not necessarily have the same understanding or prioritise the subject. This gap in knowledge affects the capacity of the training to have an impact in the application level after the provision of the workshops.

“I believe it’s educational [the training] for all existing and new recruits of fisheries officials and to better provide technical advice for decision makers, because without understanding the science behind the fisheries, I don’t think you can provide better advice and it will go against our overall long-term objectives of the ministry” Female participant in the harvest strategy training in Samoa.

Furthermore, almost three quarters of respondents (73%) reported facing learning difficulties during the workshops, most of them linked to the technical terminology and concepts, the background preparation needed and the length of the training.

“The timeframe for the training was not enough. Needs more time to understand the technical and scientific models and content of the harvest strategy” Female participant from the Solomon Islands.

The facilitators provided supplementary materials after the completion of the training. However, less than half of respondents (40%) reported that they had consulted them. Addressing the reported learning difficulties in future training can be done by making a thorough review of the materials to be used before, during and after the workshops. Ahead of the training, the facilitators could liaise with the participants to get a general idea of their profiles so they can tailor the level and contents of the workshops accordingly. Despite the need to use technical words, the facilitators could still deliver the training to fisheries officers with diverse roles in the ministries by adapting the materials and delivery method. Furthermore, the supplementary materials could be more practical, user friendly and dynamic to inspire more participants to consult them after the training. Participants could also be encouraged to review the posters, videos or presentations by following up with them in case they have any questions on these additional materials, or any other post-training queries they might have.

The ABC of lessons learned on delivering and assessing the harvest strategy workshops

The capacity-building experience and the post-training survey have provided valuable lessons. These insights serve the team as a foundation for further refinements to the capacitybuilding strategies, enabling more effective communication with the target audience, and increasing the use and application of the learnings provided in the training. The key lessons, summarised by thematic area, are listed below.

A) From conducting the training workshops

- Keep combining the regional with the national level training.

- The one-on-one country-specific conversations have proven useful to grasp more of the current situation and context of each PICT that enhance the provision of support around the harvest strategy.

- Maximise the advantages of building strong advocates and influencers during the workshop.

- Follow-up is essential for sustaining PICT engagement.

B) From data collected in the survey

- The terminology, participant profiles, training duration and timing, and agenda, are items of the training preparation to be reviewed by the team based on the feedback collected.

- There is a need to potentially review the context and setting in which the decision-makers on harvest strategy and teams operate to address it further in the training planning.

- Less than half of the participants consulted the supplementary materials. These could be improved by making them more practical, user friendly and dynamic and by using them as a reference for follow-up with participants.

C) From deploying a tracer survey

- The training facilitators and the monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL) teams must work more closely together to enhance data completion and accuracy.

- During the training, it is important to inform participants about SPC’s interest in assessing the lasting impact of the training workshops to enhance contact information and responsiveness to surveys.

- Tracer surveys should be co-designed with facilitator teams to tailor the application of knowledge questions to the context of the training subjects.

For more information

Laura Manrique, Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning Officer, SPC | [email protected]

Nan Yao, Fisheries Scientist (Management Strategy Evaluation Modeller), SPC | [email protected]

Download the full SPC Fisheries Newsletter: https://bit.ly/FNL172